01 Apr Revolutionize your Landscape and Hydrate your Land

How much should I be watering? As a landscape professional in Durango, this is a question I get asked regularly. The answer is generally the same, and that is, “stick your finger in the soil at root level to gauge moisture”. There’s no quantifiable magic formula otherwise. There are so many factors – like aspect, wind exposure, type of soil, type of plant – that truly, the only way to know whether the soil around your plant needs more water is to use your senses and monitor.

That’s one benefit that comes with hand watering with a hose as opposed to using an irrigation system. I do love you my friends and colleagues in the irrigation industry, but statistics show that 16% more water is used outdoors by households with drip systems than those without, and many plants get over watered when the settings accommodate just a few thirsty plants.

Households with their drip system on an automatic timer use 47% more water than those that do not. This is because

- Settings are too often not adjusted for seasonal changes in water needs

- They are not set to decrease output once plants are established

- Leaks are seldom noticed or repaired

- The system waters whether plants need it or not, including when it has just rained

When you create a Harvesting Landscape that you water by hand, you are intimately in touch with your plants’ needs, and water only when the plants need it, and water is dramatically conserved.

What is a Harvesting Landscape, you ask?

A Harvesting Landscape collects and maximizes the use of resources while hydrating the land. Let’s boil it down by means of contrast, and first look at it’s opposite – a Draining Landscape.

First, a Draining Landscape, Explained

A draining landscape drains off not only water, but other desirable elements as well, and dehydrates the land, causing the plants to suffer over the long term. Plants are planted on top of mounded berms of soil that is often imported. Water, nutrients, topsoil, organic matter all drain off, thanks to our reliable friend, gravity. Constant effort is required to water, fertilize, and keep the mulch in place on mounded landforms. The high maintenance nature of this common type of landscape keeps perennial bed maintenance companies like mine in business, for better or for worse.

Rain coming off a roof in a Draining Landscape is efficiently directed past plants and into landscaped drainage ways – often taking the form of constructed dry streambeds, streets, and storm drains. Flooding can be an issue when this infrastructure is overloaded, and hardscaping, such as patios, driveways, and paths, made to slope toward streets and drains, just compounds the problem.

According to Brad Lancaster’s book Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond (where much of my data is sourced), if 19 inches of rain (Durango’s average) lands on a Draining Landscape in a year, often nary a single inch is absorbed by the soil. As a result, automatic irrigation systems will often turn on even after a downpour.

A whopping 50% of residential drinking quality water in the United States is used in the landscape. Meanwhile, only 3% of water on the planet is available to humans and fresh water is slated to be much harder to come by in the near future.

Now back to a Harvesting Landscape

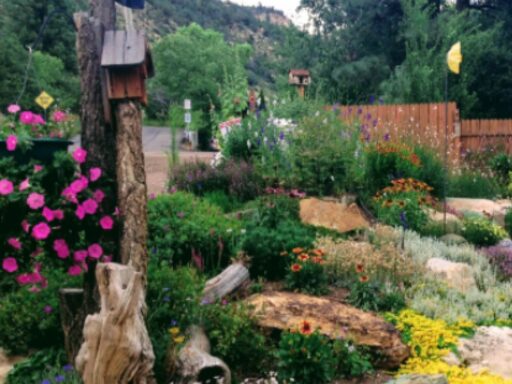

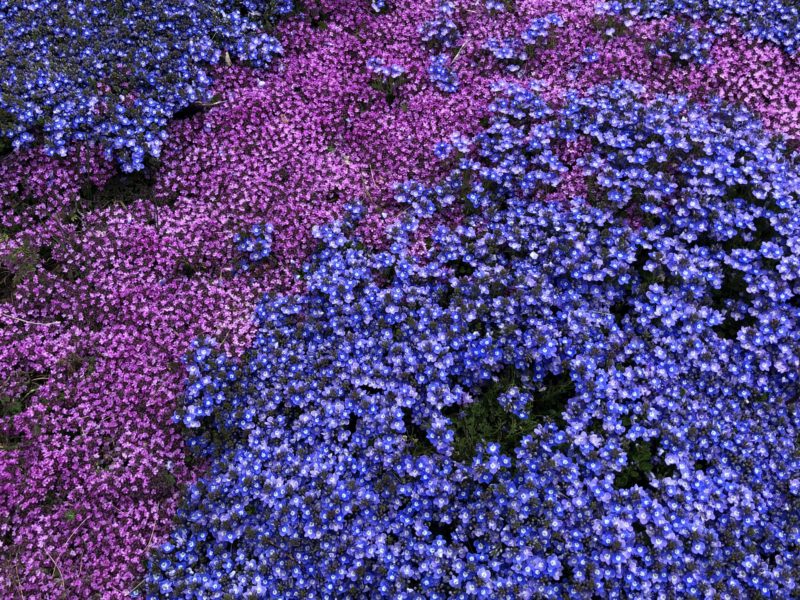

Harvesting Landscapes mimic nature where it is evident that life thrives when water lingers. Harvesting landscapes collect and retain resources while hydrating the land. In this type of landscape, plants adapted to the conditions of the site are planted within areas sculpted to be concave. These depressions effectively harvest moisture, topsoil, and organic matter, thereby passively feeding plants and watering the soil.

These sculpted concave areas direct roof runoff to the root zone of plants. Hardscape features slope in a direction that will retain water in the landscape, rather than expediting it to the street. This benefits the landscape and reduces flooding by alleviating burden on the infrastructure that may already be taxed during storm events by both water and sediment.

Creating pathways that are at a higher grade than your planting areas not only benefits the landscape by contributing water to it, but in cold climates like ours, they maintain ice-free walkways, reducing the chance of slipping.

If 19 inches of rain falls on our landscape in a year and the roof and sidewalk are equal in area to the planted portions, then the sidewalk and the roof, each, direct an extra 19 inches to our planted landscape. These impermeable surfaces triple the natural water total equalling 57 inches dedicated to hydrating the land and watering our plants over the course of a year!

When this free source of water is passively harvested by using these strategic grading techniques referred to as earthworks, there is generally enough moisture for native and adapted plants to survive and thrive once established, negating the need for costly or complicated irrigation systems and reducing problems associated with flooding. And, FYI, rain gardens and small-scale water-harvesting earthworks are, and always have been legal in Colorado.

While it takes some initial effort to sculpt your land to create passive water harvesting earthworks in keeping with Harvesting Landscape principles, over time the cost and maintenance are less than active watering systems. A Harvesting Landscape approach creates solutions to many of the most common landscape challenges our area throws at us.

So, you tell me, how much should you be watering? I dream of the day when everyone has Harvesting Landscapes and I can respond, “not at all; Mother Nature’s got this.”

To the glory of the garden! Eva

By Eva Montane, certified Landscape Designer and President of Columbine Landscapes Co

Our 2024 Newsletter Theme: The Mechanics of a Sustainable Landscape

What is a sustainable landscap...

A Natural Solution to Prevent the Need for Herbicides & Pesticides

In today’s world, where ...

How to Create Habitat for Pollinators in Your Landscape

Creating habitat for pollinato...

Myth Busting: Dry Streambeds, Cobble as Weed Control, Rototilling

MYTH #1 DRY STREAMBEDS BELONG ...

Discover the Harmonizing Effects of Infinity Gardens

Infinity gardens embrace the n...

How Rain Gardens Emulate Nature’s Hydrological Engineers: the Beaver

If you’ve been reading our n...

Is “Nonvegetative turf” a Good Alternative to Traditional Lawn?

I know it can be a challenge t...

5 Simple Ways to Fine Tune your Watering for Drought Resiliency

Drought in our region is the n...

Tired of mowing your lawn? Dig into drought ready landscaping.

Did you see this article in fr...

Fall Forward: Tricks for enhancing your landscape with bulbs

Wait, didn’t we just spring ...

What’s an Eco-Friendly Landscape Company Look Like?

Earth Day being just around th...

Now is the time for cultivating winter interest

There are so many options for ...

How to avoid the green blur and make your plants pop

Plants – especially the ones...

Lasagna Lawn Removal: How to Passively Get Rid of Lawn Over the Winter

As you may or may not know, th...

What is XERIscape & is it the same as ZEROscape, Drought Tolerant & Water-wise?

Good question. And great time ...

Durango Herald – Is Durango Doing Enough to Conserve Water?

We are proud to have been rece...

Rocky Mountain High; Touring Colorado in Garden Celebrity Style

My new friend Kit Strange and ...

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.